This above is the first few measures of what is probably one of JS Bach's most famous pieces, BWV 864, the Prelude in C Major from the Well Tempered Clavier. I guarantee that you have heard it. For those of you who read sheet music and don't recognise the title a glance at the first two bars will suffice, but for the rest, sorry, but I can't bring myself to link to a horrid midi sample that would just sound like tinkly pox vomit.

It has been used in countless ways, in endless movie and TV scores, advertising, and even in my modest if eclectic music collection I have no less than 3 versions, not including the 'straight' ones. A blues/groove/techno one, a rendition with African percussion instruments, and a chillout electronica one. The theme often gets sampled. Also, if you've ever heard a piano student practicing, then chances are you've heard it. Because of its beauty and relative simplicity it is a mainstay of piano curriculum, usually used as a milestone piece for attainment of a basic level of competency. As the full title suggests, it was written for keyboard - harpsichord or clavier in Bach's era, as the piano had only just been invented, not yet perfected, and Bach did not like it so much, but saw its potential with more development.

So, I've heard and loved it all my life. I have even played some of it on guitar (can't play piano - always had just a bit of pianist envy) but like most of Bach's work it doesn't really translate to guitar. Much is just not physically possible. Once, many many years ago, and inspired by that memory again just recently, I heard my version. The one that speaks to my heart.

Because music is not just maths. It isn't the simple arrangement of audible vibration through time - or I'd happily link to a midi sample. It is also more than the notes and hints a composer might give on expression, or rubato (although it must be said that some composers go way far into poetry with their attempts), or the dynamics of a particular instrument used. The vital key (pun!) is the performer. Yes, their technical ability counts in that they have to be able to actually complete the piece well and as effortlessly as possible, but it is more than that again. It is their interpretation, as they say; the duende, the heart, the soul they impart or divine with the piece.

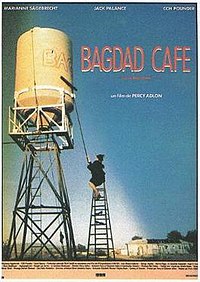

My version is played by a young musician, acting in the film, of modest technical piano ability (who it seems is now a tenor of some reknown), on a less-than-perfectly-tuned and harmonically er, interesting old upright piano, and is very basically recorded and mastered. Some might say the production values are a little amateurish. Perhaps all this was deliberate, but anyway none of it is really important. It was done for the 1987 film Bagdad Cafe (also known in Europe as Out of Rosenheim). Maybe you've seen it? The young player's name is Darron Flagg.

Oh hey! I just found a site where you can download an mp3 version from the film - allegedly. I haven't tried to do it, and can not vouch for the site's credentials, but HERE it is.

It is a truly beautiful film. For the sake of those who may not have seen it but wish to, I shall reveal nothing of consequence about it, except that the scene where this piece is finally played to completion is for me one of the most majestic 150 seconds or so of film and music ever. I have questioned myself long and hard about this (as well as short and soft - I have tried all angles) and although remembering the film moment does give some added poignancy for me, the music (which I have separately, from the otherwise mostly woeful soundtrack album) stands alone in its integrity.

So why does it so move me? Like all attempts at describing art with words, this one will ultimately fail, but it is still worth a shot. I might catch something of use as these thoughts speed fleetingly through my puny mind. I guess the short answer is simply, as if from the exasperated parent of a 4 year-old, "because it just does." But some deconstruction might uncover something about it, or me, or both.

First perhaps is that it is faithful to the original manuscript. Probably more versions than not these days have extra instruments added, harmonies imposed, thematic repetitions made or some other thing not intended by the composer. Don't get me wrong, I'm not a rabid dogmatic originalist, I'm just saying that some things are best in their original state. This is one such thing, and I think now the piano has overcome the problems Bach had with the early versions (high notes too soft, in the main, for a balanced dynamic response) he'd like it this way. The slightly tinny yet boomy piano used is entirely charming and has a quality reminiscent of a baroque instrument. It doesn't take itself too frightfully seriously, as a Steinway grand necessarily must. This helps it to be humble.

Of course, there's the playing. Some say Bach (in keeping with the habit of many of his contemporaries) intended his works to be played to a severe metronome - with a dead straight rhythm. To this I say poppycock, there is no evidence of this, it is mere supposition. Who cares anyway. And in the case of this rendition, the instances of tempo rubato (speeding up and slowing down) are quite extreme and expressive in the highest degree. This is no clockwork Bach recital. Every morsel of expressiveness is coaxed from the nearly-outclassed instrument; you can almost hear its Puffing Billy refrain to itself underneath "I think I can I think I can..." as it tries its best for its performer. And Darron Flagg does create a human moment exactly as I believe the movie's makers intended - of a child nearing manhood, with so much sensitivity and depth of insight that the world seems blind to, who has found a brief window in which he may at last truly be heard. And thus produces for me the true meaning of the piece.

The work itself. When you step back for a moment the first thing you notice is that the entire piece, right up to the final instance, is comprised of single notes. Not a single chord or even pairing. No harmony. just arpeggio, one note after another. So simple! And yet as the piece winds between the modes and relativities of its key - never straying far from C Major - the sustain of notes brings forth an eerie richness, a sense of the connectedness of past and future. Each measure is slightly different from the last, and takes you on a perfectly congruent journey. Every mood available to man, consciously or divinely so, is touched upon so briefly, so sparely, it is like a series of the greatest haiku or zen paintings that make up in their total journey The Book Of The Possible. I can feel in the 153 seconds of this performance an analog of everything that this life has to offer, even death. So short, yet enormous; so simple, yet incomprehensibly complex. Really, it's that good. Unfailingly, I shed a tear. It just all comes together.

Well, it's like this for me anyway. My particular musical background influences the way I experience music, as it would for us all. But it's not a head thing. All that wordy verbiage has come later, in some vain attempt to help my mind recover some pride after being so shockingly demoted in the presence of such great and raw emotional import and divine inspiration. Oh, poor mind. Still, I need it every now and then so best to look after it really.

That's all I can say. If you take the time to listen, I hope it gives you some pleasure too.

I shall go and listen to it now.

Aadhaar, your expression is wonderful

ReplyDeleteI'm not going to anaylise it much, you've already done that brilliantly. I had to study Bach when I did HSC music in year 11. (There was not enough student to form a year 11 class, as per usual!) I can only draw the parallels is rock music at my stage of listening. Having a distictly seperate (but still inversions of the main phrase) left hand just cant help but remind of John Entwistle, Chris Squire, Steve Vai, Eric Johnson etc. The've all taken from is timeless writing, and your right, they do not transfer well to guitar. I think it was an effort in the 80's to try and mimic these appegios and riffs, usually in metal bands. Uuuurrgggg! Terrible stuff, but it did happen as you know. It sounds the best as it was meant, and it is a beautiful Fugue. X

ReplyDeletesome things are not to demean by analysis

ReplyDeleteI too have pianist envy